Fiscal rules have come under a range of criticism in recent years in the UK and elsewhere. In general, the argument of critics has been that they encourage sub-optimal economic policy-making. For example, they have been blamed for forcing countries into counterproductive austerity to not enforcing fiscal sustainability adequately.

Despite this, fiscal rules are increasingly being adopted by countries across the world, even if they are not always followed in practice. Evidence does suggest that fiscal rules are important for fiscal sustainability but that they need to be designed right and that the overall fiscal framework – the conventions and processes that govern how fiscal policy is made – needs to be supportive of their implementation.

Economic and fiscal policy has been far from perfect since fiscal rules were introduced in the UK in 1997. The main rules in place are that public sector net debt should be on course to fall as a share of GDP in five years’ time, and that public sector borrowing should not exceed 3% of GDP in five years’ time.

A group of us at the Institute for Government – a non-partisan UK-based thinktank with a mission to improve government effectiveness – recently published a report (Strengthening the UK’s fiscal framework) analysing problems with UK fiscal policy and whether changes to the rules or how they are used could help.

‘Fiscal fiction’: the inconsistency between budgeting frameworks and fiscal rules

A salient problem in the UK over recent years has been what we refer to as ‘fiscal fiction’, whereby fiscal rules are only met through implausible plans from the government. This arises principally from an inconsistency between the horizons of the fiscal rules on one hand and the medium-term expenditure framework on the other.

The UK’s current set of fiscal rules (our eighth set since 2009 that will shortly be replaced by our ninth by the recently elected new government) includes target fiscal metrics five years ahead on a rolling basis. Plans for tax and welfare policies are also always set out on a rolling five-year basis, with forecasts scrutinised and published by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR, the UK’s independent fiscal institution).

Detailed multi-year expenditure plans on the other hand, initiated through ‘spending reviews’, typically have a much shorter time-frame. In the UK a spending review performs the usual function of reviewing existing expenditure, but also sets multi-year budgets for all government departments. Such budgets are, however, set for a period of anywhere between one and five years, and they are set on a fixed rather than a rolling basis. This means that, in the period immediately preceding a new spending review, detailed spending plans will not extend far into the future. Currently, for example, we only have departmental spending plans up to the end of March 2025. For the years of the fiscal forecast beyond that, the government provides a ‘pencilled in’ number for total government expenditure, which the OBR must take as given when reviewing the government’s plans.

UK governments have taken advantage of the inconsistency between these elements of the fiscal framework by pencilling in tight aggregate spending plans in the years not covered by a spending review, helping them to appear to be on course to meet fiscal rules which only apply in five years’ time. Crucially, the government has not needed to spell out how it would achieve these tight plans. In practice, at every spending review since 1997, except one, the government has revised the plans upwards.

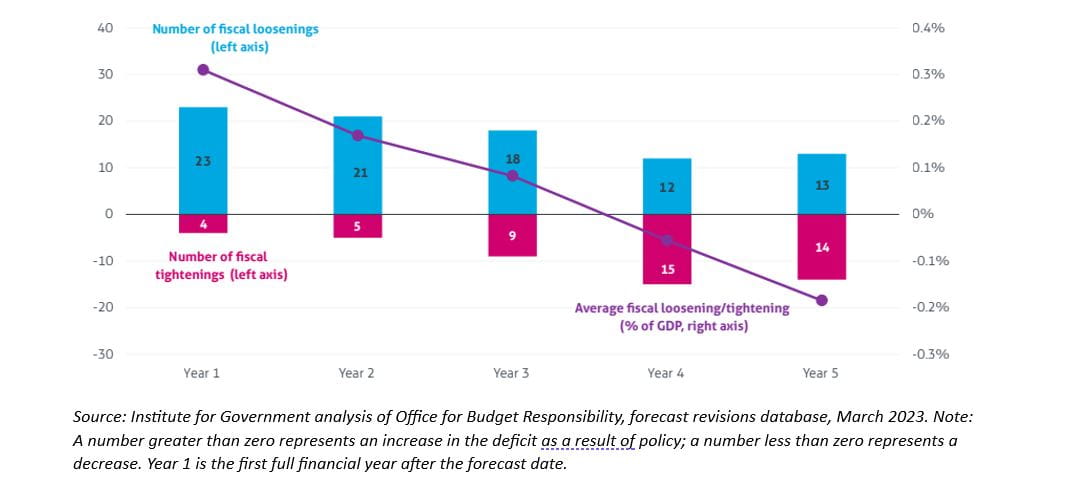

This behaviour leads the government to systematically deliver policy giveaways in the short-term while announcing unrealistic, never-to-be-delivered spending cuts in the longer term (see chart). This is damaging for fiscal sustainability. Fiscal rules only work as a discipline if they force politicians to make the difficult trade-offs necessary to meet them.

To overcome these problems, we recommend that the government moves to a medium-term expenditure framework that sets budgets for a longer time period on a rolling basis and shortens the horizon of fiscal rules from five to three years (using escape clauses to allow an appropriate degree of flexibility during crises). This would mend the hole that currently exists in the framework and ensure that fiscal rules fulfil their function.

Chart: Effects of policy on borrowing in different years of Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts, November 2010 to November 2023

Changes to the framework that can encourage more strategic and long-term fiscal policy

Our report makes further recommendations on changes to the fiscal rules and wider fiscal framework in order to address other problems beyond fiscal fiction in the policy-making process. Our main recommendation is that it is essential for the chancellor to set out a comprehensive fiscal strategy, describing how government will use fiscal policy to achieve its objectives on long-run growth, net zero, demand management, intergenerational fairness and so on. Rules should follow from this. In recent times, it appears that fiscal rules have become the strategy rather than tools to implement it.

We also recommended that the remit of the OBR should be changed through updated legislation to give it greater flexibility in its assessment of the government’s rules and performance against them, moving away from a ‘pass or fail’ model of assessment of the rules and with greater license to consider fiscal sustainability more broadly. This would allow the OBR to criticise, for example, gaming of the rules (e.g. selling assets at less than fair value), which might ensure government is consistent with meeting the letter of the rules, but not their spirit.

This should be supported by greater emphasis from the OBR on the uncertainties in the fiscal forecast, and on the longer-term effects of policies, looking beyond the usual five-year period covered by its economic and fiscal forecasts where appropriate.

The report also sets out that any set of future UK fiscal rules should:

- Treat investment differently to current spending. The UK has had relatively volatile and low levels of public investment, partly because ministers have found cutting capital investment to be less politically controversial than cuts to day-to-day spending.

- Specify the metrics targeted by rules as ranges rather than point targets, to reduce the incentives that ministers face to constantly micromanage fiscal policy as the five-year forecast evolves, which creates damaging policy uncertainty.

- Rules should include escape clauses to allow the government to deviate from them in the case of crises.

Overall, our analysis suggests that fiscal rules are an important and inevitable part of any robust fiscal framework. But they only work if they support broader, coherent fiscal objectives and are complemented by other aspects of the fiscal framework.